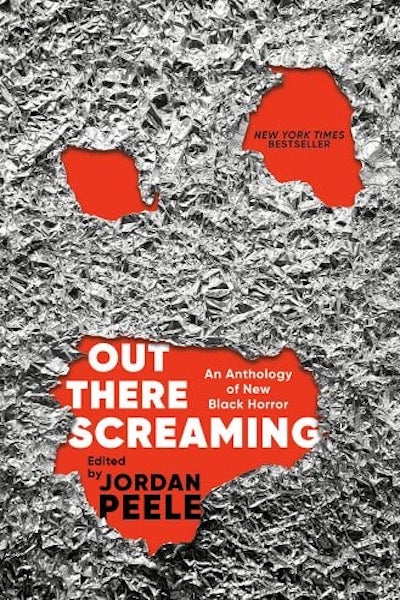

Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches. This week, we cover Rebecca Roanhorse’s “Eye and Tooth,” first published in 2023 in Jordan Peele’s Out There Screaming: An Anthology of New Black Horror. Spoilers ahead!

“First class ain’t what it used to be, so it’s not like you’re missing out.”

Zelda and Atticus Credit are flying coach to Dallas, Texas. Their clients used to fly them first class, eager to get rid of “whatever awful horror they’d conjured up.” Take the golf pro who shot his ex-wife to Swiss cheese, but she kept getting back up. He flew them first class, but then tried out an internet remedy of salting her undying corpse. That got his face eaten off before they even arrived. True hunters know it takes grave dirt to keep ghouls down.

Lately the internet provides more reliable information, so people are DIY-dispelling their monsters, however crudely. So, though the Credits can handle visitations from haints and river spirits to poltergeists, business isn’t great. And it’s a family business: every generation in the Credit family has been blessed with gifts that enable them to fight the world’s evils. Atticus has what Mama calls the Eye, the ability to live in two worlds, “Ours and Theirs.” Zelda’s is the Tooth to his Eye, the dark to his light.

From the airport, Zelda drives their rented truck through a thunderous deluge into increasingly flat and empty cow country. A dirt road leads them to an American-Gothic three-story backed by derelict farm equipment and a yellowed cornfield. “Some real Children of the Corn shit,” Zelda mutters. Atticus rouses himself, coming into “focus.” Zelda asks if he feels anything. Could be, Atticus replies, but it could also be Zelda’s “energy” interfering.

Their client, an older woman named Dolores Washington, greets them curtly and leads them to dinner. Lanky Atticus helps himself. Zelda passes. Even if she did eat things like the offered red beans and cornbread, something feels is off-putting. Also, the dining room’s packed with displays of dolls: porcelain, paper, vinyl, even corncob dolls in gingham dresses. Haughtily, Washington claims not to be a “collector” but a “creator.” Either way, Zelda doesn’t like the dolls. She likes less how Washington treats a six or seven year-old girl in a metal leg brace who comes into the room, to be dismissed with a sharp reprimand.

Washington says she’s heard the Credits are “real deal Black folks. Root workers and hoodoo queens.” Her grandmother worked with herbs, but what the Credits have is “power in [the] blood.” She challenges Atticus, their “Eye,” to divine her trouble. He tries but shakes his head, and grudgingly Washington describes a presence in the cornfield that’s been killing animals and screaming at night. She’s sure it’s no fox or cougar, though she won’t admit to actually seeing it. Zelda decides that, in spite of the continuing storm, she’ll investigate at once. Washington invites Atticus to bed down in her guestroom. Though Zelda hoped he could deploy his Eye during her absence, she sees he looks tired, even wan, and makes no protest. From the guestroom window, Zelda spots something moving in the cornfield as if on all fours.

Outside she meets the little girl from the dining room, rain-drenched and mute. She gestures for Zelda to follow her into the corn. Feeling “this kid ain’t just a kid,” Zelda complies. Soon they find a freshly killed and mangled animal. At last the girl speaks, one word: “Hungry.” Something sure was. Afraid it might still be nearby, Zelda brings the girl back inside.

Next morning, Zelda leaves Atticus still asleep and goes to the town hardware store for trapping supplies. Hoping for background information, she chats with the clerk. He’s glad to gossip. Rumor was that Dolores’s grandmother did away with Dolores’s abusive father. Dolores herself has become famous for her corncob dolls: among pictures of town celebrities is one showing Dolores with a child-sized doll adorned with a blue ribbon. But then Dolores’s granddaughter got her foot snapped off in an old animal trap and bled to death in the cornfield. With her daughter estranged, Dolores has been all alone out there.

Puzzle pieces begin snapping together in Zelda’s mind. The little girl. Washington’s talk about power in the blood. Atticus’s post-dinner somnolence. She races back to the farmhouse. A dead granddaughter couldn’t survive on random animal kills. She’d need what all revenants need: a human, especially a powerful one.

Washington’s not around, but the girl is upstairs on the bed beside Atticus, her mouth encrusted with his blood. Her leg brace is off, exposing a limb missing below the knee and corn husks protruding from her pants cuff. “Hungry,” the girl whispers. Before Zelda can act, a wooden knitting needle skewers her in the back. Washington cries that she won’t lose her grandchild!

Zelda spits back that Washington can’t have Atticus, and didn’t Washington’s granny tell her that magic always comes in twos, Light and Dark? She calls up her power, the same as runs in Atticus but “bent different.” Her fangs descend, her nails sharpen, and she roars as she rips out the knitting needle and feels her pain turn to clarifying exhilaration. Washington screams, but her raised hands can’t ward off “what’s next,” for now Zelda’s hungry, too.

The rain has stopped when Atticus, bandaged and still chalky from blood loss and Washington’s poisoned beans, makes it out to the truck. He looks at the little girl who sits beside Zelda, playing with a paper doll. Zelda says she can’t leave the girl alone. But there are rules: she’s told the kid no eating until they get home and Zelda can teach her how to hunt “proper.”

Atticus grunts, but Zelda knows he won’t fuss. Like Zelda, he knows that “sometimes the best monster hunters are monsters themselves.”

The Degenerate Dutch: “Granny told me about your family. Real deal Black folks.” And, therefore, expendable.

Weirdbuilding: Folk magic runs all through this story, from Zelda’s family to Washington’s Granny—both the supernatural kind of magic, and the practical kind that whips up tonics to “cure” abusive husbands.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

There was a period when my gamemaster refused to set role-playing scenarios past about 1999. Cell phones, he felt, were the bane of plot—if you can call for help at any time, or find out how the other half of your split party is doing, where’s the pressure to solve the problem yourself? Eventually he got over it—by the time smartphones came along, with the internet in your pocket, we all knew the shivers brought on by low battery and lack of signal. Then there’s the modern gothic surrealism of disinformation bubbles, of the internet as portal to the uncanny—or Zelda’s (no relation) complaint that YouTube videos take work away from traditional practitioners, with only a small chance of getting your face eaten. Maybe that irritation with modern technology is why she doesn’t carry a cellphone—leaving room for anxious races to climactic confrontations.

Zelda, it’s clear right away, only cares about clients getting eaten in-so-far as it interferes with being paid. In general, she has little interest in her clients as people worthy of sympathy. They’re monsters, hiring monster hunters to hunt monsters that they’ve created or summoned themselves. And the story’s final line comes as little surprise. From the moment we learn that Zelda can’t eat airplane food—not for the same reasons the rest of us avoid it—it seems pretty clear that her appetites are not those of an ordinary human. Her dream of waking up next to a bloody carcass seems more temptation than nightmare. So I spent most of the time going “Vampire, ghoul, werewolf, zombie…?” like some off-kilter kid’s game of pulling petals.

She’s a monster with an appreciation for culture, though—not only horror flicks like Children of the Corn with its monstrous rural kids, but classic paintings like Andrew Wyeth’s Christina’s World. That’s “that one with the girl in the field reaching for something she ain’t never gonna get.” Of the model, MOMA says: “As a young girl, [Anna Christina] Olson developed a degenerative muscle condition—possibly polio—that left her unable to walk. She refused to use a wheelchair, preferring to crawl, as depicted here, using her arms to drag her lower body along.” Perhaps Zelda has a touch of the Eye herself, given that she’s about to encounter (and adopt) a monstrous rural kid with mobility challenges.

The most monstrous monster here—as appears to be usual for Zelda—is the client. I once IDed a bad guy way before the Shocking Reveal because he threw a fit about kids enjoying Batman comics, and I pegged Washington the first time she complained about muddy floors. The woman is living out in deep farmland, but has delusions of Armitage-ness. Wanting to keep her granddaughter undead at the cost of strangers’ lives: sympathetic. Whining at those strangers about her pristine floors: nope. (Sorry, yes, I know that’s a different Jordan Peele movie.)

Making creepy corn dolls: also nope. Really, I feel bad for all the innocent doll collectors out there with houses full of staring glass eyes—horror has given them a bad rap. Though the fear apparently comes naturally: my son, who has never seen Chucky or been offered my Tara Campbell collection, consistently makes me hide away decorative dolls in AirBnBs. Ellen Datlow too has a doll-focused horror anthology—and yet. There are people whose uncanny valley is very narrow, and most of them never even once create a half-doll revenant to try and stave off the death of a loved one. Yet another point against Washington.

Final point against: she could have just asked. Zelda turns out to have exactly the expertise needed, and all the sympathy in the world for a supernaturally-hungry kid. If Washington had considered her “real deal” hunters as something other than prey, there’d have been much less need for poisons and knives. But then, if people like her could consider people like Zelda and Atticus for something beyond their immediate utility, they might’ve made a better case for Zelda’s sympathy a long time ago.

Anne’s Commentary

What with the thunderstorm that was raging when the Credits arrived at Dolores Washington’s house, I doubt Zelda thought to check the front porch ceiling. A safe bet is that it wasn’t painted the color called haint blue. The Gullah people of coastal Georgia and South Carolina traditionally painted porches, window frames, and shutters with an indigo-based blue-green. They believed doing so would prevent haints (ghosts and malicious spirits) from entering a house; either the haint would mistake this soft pale blue for the sky and pass on, or would shy away as from water, which haints can’t cross. Eventually other Southerners adopted the custom. Who wants haints in the house? Or wasps in their porchside supper—like haints, bugs are supposed to confuse a blue ceiling for the sky and to preferentially fly towards it.

I guess haint blue can discourage ghosts—my porch ceiling sports the color, and I haven’t had any ghosts yet. Wasps, sadly, aren’t fooled. They pervade the porch whenever food is available. So, yeah, blue paint for revenants, screens for bugs. In case you want to beef up your own supernatural wards, Southern Living has an article listing the exact paint brands and colors to do the job.

But if, like Dolores, you have a haint for a (more or less welcome) family member, keep away from the blue spectrum altogether. Stick to whites, or if you’re trendier, sunflower yellow. Spirits, and wasps, love that color.

What are the odds that the main character in this week’s story would have the same name as the main character in last week’s story? Not high, I’d say, particularly if the name is an uncommon one. In 2023, Zelda ranked 556th in popularity among female baby names. However, according to its Teutonic origins, Zelda signifies a woman warrior. Where monster hunting is concerned, Roanhorse’s and Gladwell’s Zeldas are that in spades. Perhaps the name was chosen for this meaning?

I’m not sure whether Last Exit Zelda’s superpower, or knack, is inborn or acquired, though it’s suggestive that cousins Sal and June develop—or express— the same knack after being exposed to the Beyond. “Eye & Tooth’s” Zelda definitely has a genetically-granted superpower—as Dolores puts it, it’s in her blood. The Credits’ powers define them: Atticus is an Eye, the organ associated both with actual light and with the moral concept of Lightness, the Seen, the Understood. Whereas Zelda is a Tooth, the organ associated with biting, killing, devouring and the moral concept of Darkness, the Taken, the Mystery.

I’ve always been deeply creeped out by these lines from Stephen King’s The Stand: “There were worse things than crucifixion [villain Flagg’s preferred method of execution.] There were teeth [another method of which Flagg was only too capable of employing.]” Tooth-Zelda convinces me further of the terror inherent in dentition.

The Eye and the Tooth share the work of defense, the first via perception, the second via action. Atticus’s ability to see into realms beyond the mundane is a major asset to the hunting pair. It’s also a weakness, for which Zelda compensates with her practical skills and a predator’s heightened awareness of her umwelt. If the Credit siblings could always work side by side, or back to back, they’d be unbeatable.

The catch for storytellers: Unbeatable protagonists make for boring narratives. Roanhorse has a surefire way around this catch: Atticus and Zelda are both monster-hunters, but Zelda is herself a monster. When she’s close to her brother, her monster-vibes can interfere with his efforts to detect other monsters, their targets. So separate they sometimes must. Another plot-nurturing workaround is that Zelda can’t always act on her monsterly intuitions and impulses. Letting her fangs and claws out around clients would be bad for business; in spite of getting all kinds of bad feelings about Dolores, she has to be polite. Dolores is rude and condescending. Dolores raises Zelda’s hackles by mistreating her granddaughter. But Zelda must remember that Dolores has a fat wad of cash in her cleavage. When you’re a monster dealing with humans, you sometimes have to let “professionalism” trump instincts. Right?

Not this time, because it almost results in Atticus becoming revenant-fodder.

Oh well, every system has its flaws. Magic, Zelda tells Dolores, “always comes in twos. Light and Dark. Eye and Tooth.” On the positive side, the Credits know that “sometimes the best monster hunters are monsters themselves.” Who can know a monster better than another monster? A legitimate corollary: Who can empathize with a monster better than another monster? This isn’t to say that humans can’t at least sympathize with monsters. Atticus isn’t happy about Zelda adopting Dolores’s revenant grandkid, but he won’t try to stop her.

Besides, humans are often more monstrous than the monsters. Take Dolores, for instance.

Please, take Dolores, including any scraps Zelda may have left.

Next week, it’s Cowboys Versus Tentacles in chapters 33-34 of Max Gladstone’s Last Exit.